Cloud Computing: Billowing Toward Data Ownership - Part II

Tuesday, July 15, 2008 at 3:12PM

Tuesday, July 15, 2008 at 3:12PM [Return to Part I]

Cloud Computing's Achilles Heel

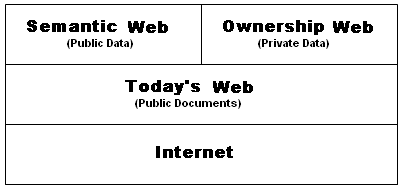

Death of Achilles Peter Paul Rubens 1630-1635The boom in the data center industry is building the Cloud where the conventional wisdom is that the software services of the Semantic Web will thrive. The expansion of the Cloud is believed to augur well that distributed data within the Cloud will come to substitute to some extent - perhaps substantially so - for data currently distributed outside of the Cloud. But the boom is being built upon a privacy paradigm employed by online companies that allows them to use Web cookies for collecting a wide variety of information about individual usage of the Internet. This assumption is the Cloud’s Achilles’ heel. It is an assumption that threatens to keep the Cloud from fully inflating beyond publicly available information sources.

I'm mulling over a more indepth discussion of Web cookies for a final Part III to this multi-part series. In the meantime the focus of today's blog is that a more likely consequence of the Cloud is that as people and businesses consider moving their computer storage and services into the Cloud, their direct technological control of information becomes more and more of a competitive driver. As blogged in Part I, the online company that figures out ways of building privacy mechanisms into its compliance systems will be putting itself at a tremendous competitive advantage for attracting the services to operate in the Cloud. But puzzlement reigns as to how to connect the Cloud with new pools of the data (mostly non-artistic) that is private, confidential and classified.

Semantic Web: What’s Right About the Vision

What’s right about the Semantic Web is that its most highly funded visionaries have envisioned beyond a Web of documents to a ‘Data Web’. Here are two examples. A Web of scalably integrated data employing object registries envisioned by Metaweb Technologies’ Danny Hillis. A Web of granularly linked, ontologically defined, data objects envisioned by Radar Network’s Nova Spivack.

Click on the thumbnail image to the left and you will see in more detail what Hillis envisions. That is, a database represented as a labeled graph, where data objects are connected by labeled links to each other and to concept nodes. For example, a concept node for a particular category contains two subcategories that are linked via labeled links "belongs-to" and "related-to" with text and picture. An entity comprises another concept that is linked via labeled links "refers-to," "picture-of," "associated-with," and "describes" with Web page, picture, audio clip, and data. For further information, see the blogged entry US Patent App 20050086188: Knowledge Web (Hillis, Daniel W. et al).

Click on the thumbnail image to the left and you will see in more detail what Hillis envisions. That is, a database represented as a labeled graph, where data objects are connected by labeled links to each other and to concept nodes. For example, a concept node for a particular category contains two subcategories that are linked via labeled links "belongs-to" and "related-to" with text and picture. An entity comprises another concept that is linked via labeled links "refers-to," "picture-of," "associated-with," and "describes" with Web page, picture, audio clip, and data. For further information, see the blogged entry US Patent App 20050086188: Knowledge Web (Hillis, Daniel W. et al).

Click on the thumbnail image to the right and you will see in more detail what Spivack envisions. That is, a picture of a Data Record with an ID and fields connected in one direction to ontological definitions in another direction to other similarly constructed data records with there own fields connected in one direction to ontological definitions, etc. These data records - or semantic web data - are nothing less than self-describing, structured data objects that are atomically (i.e., granularly) connected by URIs. For more information, see the blogged entry, US Patent App 20040158455: Methods and systems for managing entities in a computing device using semantic objects (Radar Networks).

Click on the thumbnail image to the right and you will see in more detail what Spivack envisions. That is, a picture of a Data Record with an ID and fields connected in one direction to ontological definitions in another direction to other similarly constructed data records with there own fields connected in one direction to ontological definitions, etc. These data records - or semantic web data - are nothing less than self-describing, structured data objects that are atomically (i.e., granularly) connected by URIs. For more information, see the blogged entry, US Patent App 20040158455: Methods and systems for managing entities in a computing device using semantic objects (Radar Networks).

Furthermore, Hillis and Spivack have studied the weaknesses of relational database architecture when applied to globally diverse users who are authoring, storing and sharing massive amounts of data, and they have correctly staked the future of their companies on object-oriented architecture. See, e.g., the blogged entries, Efficient monitoring of objects in object-oriented database system which interacts cooperatively with client programs and Advantages of object oriented databases over relational databases. They both define the Semantic Web as empowering people across the globe to collaborate toward the building of bigger, and more statistically reliable, observations about things, concepts and relationships.

Click on the thumbnail to the left for a screen shot of a visualization and interaction experiment produced by Moritz Stefaner for his 2007 master's thesis, Visual tools for the socio–semantic web. See the blogged entry, Elastic Tag Mapping and Data Ownership. Stefaner posits what Hillis and Spivack would no doubt agree with - that the explosive growth of possibilities for information access and publishing fundamentally changes our way of interaction with data, information and knowledge. There is a recognized acceleration of information diffusion, and an increasing process of granularizing information into micro–content. There is a shift towards larger and larger populations of people producing and sharing information, along with an increasing specialization of topics, interests and the according social niches. All of this appears to be leading to a massive growth of space within the Cloud for action, expression and attention available to every single individual.

Click on the thumbnail to the left for a screen shot of a visualization and interaction experiment produced by Moritz Stefaner for his 2007 master's thesis, Visual tools for the socio–semantic web. See the blogged entry, Elastic Tag Mapping and Data Ownership. Stefaner posits what Hillis and Spivack would no doubt agree with - that the explosive growth of possibilities for information access and publishing fundamentally changes our way of interaction with data, information and knowledge. There is a recognized acceleration of information diffusion, and an increasing process of granularizing information into micro–content. There is a shift towards larger and larger populations of people producing and sharing information, along with an increasing specialization of topics, interests and the according social niches. All of this appears to be leading to a massive growth of space within the Cloud for action, expression and attention available to every single individual.

Semantic Web: What’s Missing from the Vision

Inskeep: "Is somebody who runs a business, who used to have a filing cabinet in a filing room, and then had computer files and computer databases, really going to be able or want to take the risk of shipping all their files out to some random computer they don't even know where it is and paying to rent storage that way?"

Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the widely recognized inventor of the Web, and Director of the W3C, is every bit as perplexed about data ownership. In Data Portability, Traceability and Data Ownership - Part IV I referenced a recent interview excerpt from March, 2008, initiated by interviewer Paul Miller of ZDNet, in which Berners-Lee does acknowledge data ownership fear factors.

Miller: “You talked a little bit about people's concerns … with loss of control or loss of credibility, or loss of visibility. Are those concerns justified or is it simply an outmoded way of looking at how you appear on the Web?”

Berners-Lee: “I think that both are true. In a way it is reasonable to worry in an organization … You own that data, you are worried that if it is exposed, people will start criticizing [you] ….

So, there are some organizations where if you do just sort of naively expose data, society doesn't work very well and you have to be careful to watch your backside. But, on the other hand, if that is the case, there is a problem. [T]he Semantic Web is about integration, it is like getting power when you use the data, it is giving people in the company the ability to do queries across the huge amounts of data the company has.

And if a company doesn't do that, then, it will be seriously disadvantaged competitively. If a company has got this feeling where people don't want other people in the company to know what is going on, then, it has already got a problem ….(emphasis added)

In other words, 'do the right thing', collegially share your data and everything will be OK. If only the real world worked that way, then Berners-Lee would be spot on. In the meantime, there is a ready answer.

Ownership Web

For the Semantic Web to reach its full potential in the Cloud, it must have access to more than just publicly available data sources. It must find a gateway into the closely-held, confidential and classified information that people consider to be their identity, that participants to complex supply chains consider to be confidential, and that governments classify as secret. Only with the empowerment of technological ‘data ownership’ in the hands of people, businesses, and governments will the Semantic Cloud make contact with a horizon of new, ‘blue ocean’ data.

The Ownership Web would be separate from the Semantic Web, though semantically connected as layer of distributed, enterprise-class web platforms residing in the Cloud.

The Ownership Web would contain diverse registries of uniquely identified data elements for the direct authoring, and further registration, of uniquely identified data objects. Using these platforms people, businesses and governments would directly host the authoring, publication, sharing, control and tracking of the movement of their data objects.

The technological construct best suited for the dynamic of networked efficiency, scalability, granularity and trustworthy ownership is the data object in the form of an immutable, granularly identified, ‘informational’ object.

A marketing construct well suited to relying upon the trustworthiness of immutable, informational objects would be the 'data bank'.

Data Banking

As blogged in Part I ...

People are comfortable and familiar with monetary banks. That’s a good thing because without people willingly depositing their money into banks, there would be no banking system as we know it. By comparison, we live in a world that is at once awash in on-demand information courtesy of the Internet, and at the same time the Internet is strangely impotent when it comes to information ownership.

In many respects the Internet is like the Wild West because there is no information web similar to our monetary banking system. No similar integrated system exists for precisely and efficiently delivering our medical records to a new physician, or for providing access to a health history of the specific animal slaughtered for that purchased steak. Nothing out there compares with how the banking system facilitates gasoline purchases.

If an analogy to the Wild West is apropos, then it is interesting to reflect upon the history of a bank like Wells Fargo, formed in 1852 in response to the California gold rush. Wells Fargo wasn’t just a monetary bank, it was also an express delivery company of its time for transporting gold, mail and valuables across the Wild West. While we are now accustomed to next morning, overnight delivery between the coasts, Wells Fargo captured the imagination of the nation by connecting San Francisco and the East coast with its Pony Express. As further described in Banking on Granular Information Ownership, today’s Web needs data banks that do for the on-going gold rush on information what Wells Fargo did for the Forty-niners.

Banks meet the expectations of their customers by providing them with security, yes, but also credibility, compensation, control, convenience, integration and verification. It is the dynamic, transactional combination of these that instills in customers the confidence that they continue to own their money even while it is in the hands of a third-party bank.

A data bank must do no less.

Ownership Web: What's Philosophically Needed

In truth, it will probably vary depending upon what kind of data bank we are talking about. Data ownership will be one thing for personal health records, another for product supply chains, and yet another for government classified information. And that's just for starters because there will no doubt be niches within niches, each with their own interpretation of data ownership. But the philosophical essence of the Ownership Web that will cut across all of these data banks will be this:

- That information must be treated either or both as a tangible, commercial product or banked, traceable money.

The trustworthiness of information is crucial. Users will not be drawn to data banks if the information they author, store, publish and access can be modified. That means that even the authors themselves must be proscribed from modifying their information once registered with the data bank. Their information must take on the immutable characteristic of tangible, traceable property. While the Semantic Web is about the statistical reliability of data, the Ownership Web is about the reliability of data, period.

Ownership Web: What's Technologically Needed

What is technologically required is a flexible, integrated architectural framework for information object authoring and distribution. One that easily adjusts to the definition of data ownership as it is variously defined by the data banks serving each social network, information supply chain, and product supply chain. Users will interface with one or more ‘data banks’ employing this architectural framework. But the lowest common denominator will be the trusted, immutable informational objects that are authored and, where the definition of data ownership permits, controllable and traceable by each data owner one-step, two-steps, three-steps, etc. after the initial share.

Click on the thumbnail to the left for the key architectural features for such a data bank. They include a common registry of standardized data elements, a registry of immutable informational objects, a tracking/billing database and, of course, a membership database. This is the architecture for what may be called a Common Point Authoring™ system. Again, where the definition of data ownership permits, users will host their own 'accounts' within a data bank, and serve as their own 'network administrators'. What is made possible by this architectural design is a distributed Cloud of systems (i.e., data banks). The overall implementation would be based upon a massive number of user interfaces (via API’s, web browsers, etc.) interacting via the Internet between a large number of data banks overseeing their respective enterprise-class, object-oriented database systems.

Click on the thumbnail to the left for the key architectural features for such a data bank. They include a common registry of standardized data elements, a registry of immutable informational objects, a tracking/billing database and, of course, a membership database. This is the architecture for what may be called a Common Point Authoring™ system. Again, where the definition of data ownership permits, users will host their own 'accounts' within a data bank, and serve as their own 'network administrators'. What is made possible by this architectural design is a distributed Cloud of systems (i.e., data banks). The overall implementation would be based upon a massive number of user interfaces (via API’s, web browsers, etc.) interacting via the Internet between a large number of data banks overseeing their respective enterprise-class, object-oriented database systems.

Click on the thumbnail to the right for an example of an informational object and its contents as authored, registered, distributed and maintained with data bank services. Each comprises a unique identifier that designates the informational object, as well as one or more data elements (including personal identification), each of which itself is identified by a corresponding unique identifier. The informational object will also contain other data, such as ontological formatting data, permissions data, and metadata. The actual data elements that are associated with a registered (and therefore immutable) informational object would be typically stored in the Registered Data Element Database (look back at 124 in the preceding thumbnail). That is, the actual data elements and are linked via the use of pointers, which comprise the data element unique identifiers or URIs. Granular portability is built in. For more information see the blogged entry US Patent 6,671,696: Informational object authoring and distribution system (Pardalis Inc.).

Click on the thumbnail to the right for an example of an informational object and its contents as authored, registered, distributed and maintained with data bank services. Each comprises a unique identifier that designates the informational object, as well as one or more data elements (including personal identification), each of which itself is identified by a corresponding unique identifier. The informational object will also contain other data, such as ontological formatting data, permissions data, and metadata. The actual data elements that are associated with a registered (and therefore immutable) informational object would be typically stored in the Registered Data Element Database (look back at 124 in the preceding thumbnail). That is, the actual data elements and are linked via the use of pointers, which comprise the data element unique identifiers or URIs. Granular portability is built in. For more information see the blogged entry US Patent 6,671,696: Informational object authoring and distribution system (Pardalis Inc.).

Ownership Web: Where Will It Begin?

AristotleMetaweb Technologies is a pre-revenue, San Francisco start-up developing and patenting technology for a semantic ‘Knowledge Web’ marketed as Freebase™. Philosophically, Freebase is a substitute for a great tutor, like Aristotle was for Alexander. Using Freebase users do not modify existing web documents but instead annotate them. The annotations of Amazon.com are the closest example but Freebase further links the annotations so that the documents are more understandable and more findable. Annotations are also modifiable by their authors as better information becomes available to them. Metaweb characterizes its service as an open, collaboratively-edited database (like Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) of cross-linked data but it is really very much a next generation competitor to Google.

Not that Hillis hasn't thought about data ownership. He has. You can see it in an interview conducted by his patent attorney and filed on December 21, 2001 in the provisional USPTO Patent Application 60/343,273:

Danny Hillis: "Here's another idea that's super simple. I've never seen it done. Maybe it's too simple. Let's go back to the terrorist version [of Knowledge Web]. There's a particular problem in the terrorist version that the information is, of course, highly classified .... Different people have some different needs to know about it and so on. What would be nice is if you ... asked for a piece of information. That you [want access to an] annotation that you know exists .... Let's say I've got a summary [of the annotation] that said, 'Osama bin Laden is traveling to Italy.' I'd like to know how do you know that. That's classified. Maybe I really have legitimate reasons for that. So what I'd like to do, is if I follow a link that I know exists to a classified thing, I'd like the same system that does that to automatically help me with the process of getting the clearance to access that material." [emphasis added]

What Hillis was tapping into just a few months after 9/11 is just as relevant to today's information sharing needs.

In the War on Terror the world is still wrestling with classified information exchange between governments, between agencies within governments, and even between the individuals making up the agencies themselves. Fear factors revolving around data ownership – not legal ownership, but technological ownership – create significant frictions to information sharing throughout these Byzantine information supply chains.

And then, in this era of both de facto and de jure deregulation, there are the international product supply chains providing dangerous toys and potential ‘mad cow’ meat products to unsuspecting consumers. Unscrupulous supply chain participants will always hide in the ‘fog’ of their supply chains. The manufacturers of safe products want to differentiate themselves from the manufacturers of unsafe products. But, again, fear factors keep the good manufacturers from posting information online that may put them at a competitive disadvantage to downstream competitors.

I'm painting a large picture here but what Hillis is talking about is not limited to the bureaucratic ownership of data but to matching up his Knowledge Web with another system - like the Ownership Web - for automatically working out the data ownership issues.

But bouncing around ideas about how we need data ownership is not the same as developing methods or designs to solve it. What Hillis non-provisionally filed, subsequent to his provisional application, was the Knowledge Web (aka Freebase) application. Because of its emphasis upon the statistical reliability of annotations, Knowledge web's IP is tailored made for the Semantic Web. See the blogged entry US Patent App 20050086188: Knowledge Web (Hillis, Daniel W. et al). And because the conventional wisdom within Silicon Valley is that the Semantic Web is about to emerge, Metaweb is being funded like it is “the next big thing”. Metaweb’s Series B raised $42.4M more in January, 2008. What Hillis well recognizes is that as Freebase strives to become the premier knowledge source for the Web, it will need access to new, blue oceans of data residing within the Ownership Web.

Radar Networks may be the “next, next big thing”. Also a pre-revenue San Francisco start-up, its bankable founder, Nova Spivack, has gone out of his way to state that his product Twine™ is more like a semantic Facebook while Metaweb’s Freebase is more like a semantic Wikipedia. Twine employs W3C standards in a community-driven, bottom up process, from which mappings are created to infer a higher resolution (see thumbnail to the right) of semantic equivalences or connections among and between the data inputted by social networkers. Again, this data is modifiable by the authors as better information becomes available to them. Twine holds four pending U.S. patent applications though none of these applications. See the blogged entry US Patent App 20040158455: Methods and systems for managing entities in a computing device using semantic objects (Radar Networks). Twine’s Series B raised $15M-$20M in February, 2008 following on the heels of Metaweb's latest round. Twine’s approach in its systems and its IP is to emphasize perhaps a higher resolution Web than that of MetaWeb. Twine and the Ownership Web should be especially complimentary to each other in regard to object granularity. You can see this, back above, in the comparative resemblance between the thumbnail image of Spivack's Data Record ID object with the thumbnail image of Pardalis' Informational Object. Nonetheless, the IP supportive of Twine, like that Hillis' Knowledge Web, places a strong emphasis upon the statistical reliability of information. Twine's IP is tailored made for the Semantic Web.

Radar Networks may be the “next, next big thing”. Also a pre-revenue San Francisco start-up, its bankable founder, Nova Spivack, has gone out of his way to state that his product Twine™ is more like a semantic Facebook while Metaweb’s Freebase is more like a semantic Wikipedia. Twine employs W3C standards in a community-driven, bottom up process, from which mappings are created to infer a higher resolution (see thumbnail to the right) of semantic equivalences or connections among and between the data inputted by social networkers. Again, this data is modifiable by the authors as better information becomes available to them. Twine holds four pending U.S. patent applications though none of these applications. See the blogged entry US Patent App 20040158455: Methods and systems for managing entities in a computing device using semantic objects (Radar Networks). Twine’s Series B raised $15M-$20M in February, 2008 following on the heels of Metaweb's latest round. Twine’s approach in its systems and its IP is to emphasize perhaps a higher resolution Web than that of MetaWeb. Twine and the Ownership Web should be especially complimentary to each other in regard to object granularity. You can see this, back above, in the comparative resemblance between the thumbnail image of Spivack's Data Record ID object with the thumbnail image of Pardalis' Informational Object. Nonetheless, the IP supportive of Twine, like that Hillis' Knowledge Web, places a strong emphasis upon the statistical reliability of information. Twine's IP is tailored made for the Semantic Web.

Dossia is a private consortium pursuing the development of a national, personally controlled health record (PCHR) system. Dossia is also governed by very large organizations like AT&T, BP America, Cardinal Health, Intel, Pitney Bowes and Wal-Mart. In September, 2007, Dossia outsourced development to the IndivoHealth™ PCHR system. IndivoHealth, funded from public and private health grants, shares Pardalis' philosophy that "consumers are managing bank accounts, investments, and purchases online, and … they will expect this level of control to be extended to online medical portfolios." IndivoHealth empowers patients with direct access to their centralized electronic medical records via the Web.

But given the current industry needs for a generic storage model, the IndivoHealth medical records, though wrapped in an XML structure (see the next paragraph), are essentially still just paper documents in electronic format. IndivoHealth falls far short of empowering patients with the kind of control that people intuitively recognize as ‘ownership’. See US Patent Application 20040199765 entitled System and method for providing personal control of access to confidential records over a public network in which access privileges include "reading, creating, modifying, annotating, and deleting." And it reasonably follows that this is one reason why personal health record initiatives like those of not just Dossia, but also Microsoft’s HealthVault™ and GoogleHealth™, are not tipping the balance. For Microsoft and Google another reason is that they so far have not been able to think themselves out of the silos of the current privacy paradigm. The Ownership Web is highly disruptive of the prevailing privacy paradigm because it empowers individuals with direct control over their radically standardized, immutable data.

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is the main international standards organization for the World Wide Web. W3C is headed by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, creator of the first web browser and the primary originator of the Web specifications for URL, HTTP and HTML. These are the principal technologies that form the basis of the World Wide Web. W3C has further developed standards for XML, SPARQL, RDF, URI, OWL, and GRDDL with the intention of facilitating the Semantic Web. While Berners-Lee has described in his own words (above) his perplexity about data ownership, nonetheless, the data object standards created by the W3C should be more than friendly to an Ownership Web employing object-oriented architecture. Surely, in Common Point Authoring™ will be found many of the ‘best of breed’ standards for an Ownership Web that is most complimentary to the emerging Semantic Web.

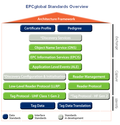

EPCglobal is a private, standards setting consortium governed by very large organizations like Cisco Systems, Wal-Mart, Hewlett-Packard, DHL, Dow Chemical Company, Lockheed Martin, Novartis Pharma AG, Johnson & Johnson, Sony Corporation and Proctor & Gamble. EPCglobal is architecting essential, core services (see EPCglobal's Architectural Framework in the thumbnail to the right) for tracking physical products identified by unique electronic product codes (including RFID tags) across and within enterprise-scale, relational database systems controlled by large organizations.

EPCglobal is a private, standards setting consortium governed by very large organizations like Cisco Systems, Wal-Mart, Hewlett-Packard, DHL, Dow Chemical Company, Lockheed Martin, Novartis Pharma AG, Johnson & Johnson, Sony Corporation and Proctor & Gamble. EPCglobal is architecting essential, core services (see EPCglobal's Architectural Framework in the thumbnail to the right) for tracking physical products identified by unique electronic product codes (including RFID tags) across and within enterprise-scale, relational database systems controlled by large organizations.

Though it would be a natural extension to do so, EPCglobal has yet to envision providing its large organizations (and small businesses, individual supply chain participants and even consumers) with the ability to independently author, track, control and discover granularly identified informational products. See the blogged entry EPCglobal & Prescription Drug Tracking. It is not difficult to imagine that the Semantic Web, without a complimentary Ownership Web, would frankly be abhorrent to EPCglobal and its member organizations. For the Semantic Web to have any reasonable chance of connecting itself into global product and service supply chains, it must work through the Ownership Web.

Ownership Web: Where It Will Begin

The Ownership Web will begin along complex product and service supply chains where information must be trustworthy, period. Statistical reliability is not enough. And, in fact, the Ownership Web is beginning to form along the most dysfunctional of information supply chains. But that's for discussion in later blogs, as the planks of the Ownership Web are nailed into place, one by one.

[This concludes Part II of a three part series. On to Part III.]

CPA,

CPA,  Cloud Computing,

Cloud Computing,  Data Banking,

Data Banking,  Electronic Product Codes,

Electronic Product Codes,  First Movers,

First Movers,  Funding activities,

Funding activities,  Granularity,

Granularity,  Healthcare,

Healthcare,  Informational Objects,

Informational Objects,  Intellectual Properties,

Intellectual Properties,  Object-orientation,

Object-orientation,  Ownership,

Ownership,  Privacy,

Privacy,  RFID,

RFID,  SaaS,

SaaS,  Semantic Trust,

Semantic Trust,  Social Networking,

Social Networking,  Standards,

Standards,  Supply Chains,

Supply Chains,  Visualization,

Visualization,  XML

XML