A New Way of Looking at Information Sharing in Supply & Demand Chains

Friday, August 5, 2011 at 11:35AM

Friday, August 5, 2011 at 11:35AM The Internet is achieved via layered protocols. Transmitted data, flowing through these layers are enriched with metadata necessary for the correct interpretation of the data presented to users of the Web. Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the Web says, “The Web was originally conceived as a tool for researchers who trusted one another implicitly …. We have been living with the consequences ever since ….” “[We need] to provide Web users with better ways of determining whether material on a site can be trusted ….”

Our lives have nonetheless become better as a result of Web service providers like Google and Facebook. Consumers are now conditioned to believe that they can – or should be able to - search and find information about anything, anytime. But the service providers dictate their quality of service in a one-way conversation that exploits the advantages of the Web as it exists. What may be considered trustworthy content is limited to that which is dictated by the service providers. The result is that consumers cannot find real-time, trustworthy information about much of anything.

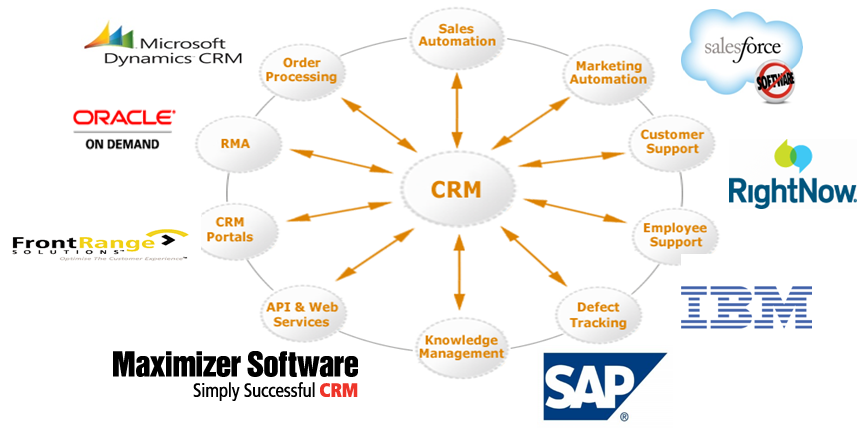

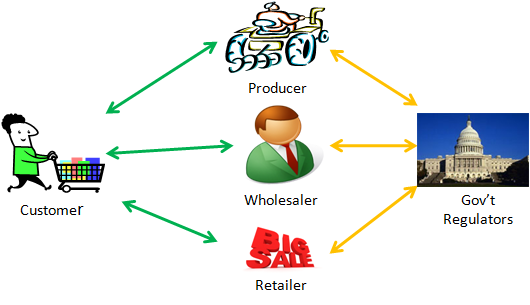

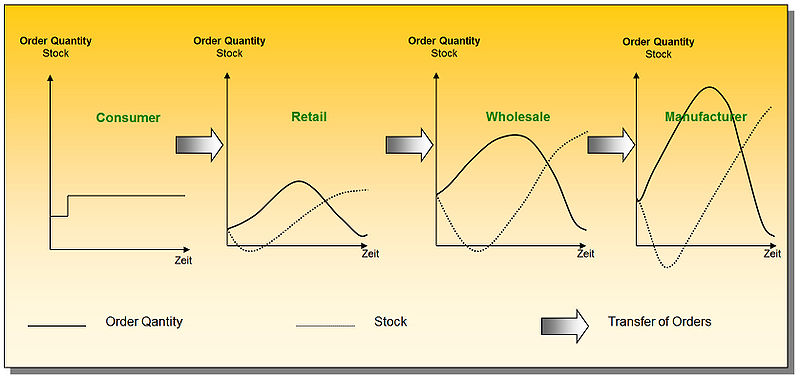

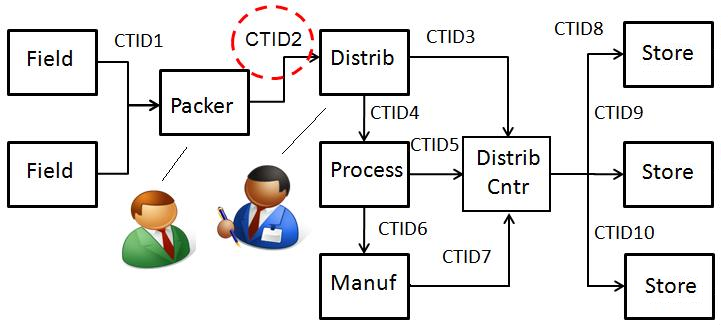

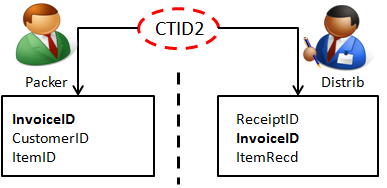

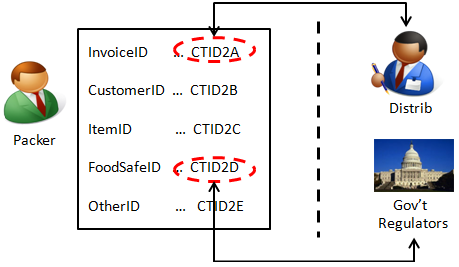

Despite all the work in academic research there is still no industry solution that fully supports the sharing of proprietary supply chain product information between “data silos”. Industry remains in the throes of one-up/one down information sharing when what is needed is real-time “whole chain” interoperability. The Web needs to provide two-way, real-time interoperability in the content provided by information producers. Immutable objects have heretofore been traditionally used to provide more efficient data communications between networked machines, but not between information producers. Now researchers are innovatively coming up with new ways of using immutable objects in interoperable, two-way communications between information content providers.

A New Way of Looking at Information Sharing in Supply & Demand chains

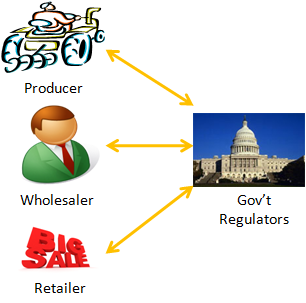

Pardalis’ protocols for immutable informational objects make possible a value chain of two-way, interoperable sharing that makes information more available, trustworthy, and traceable. This, in turn, incentivizes increases in the quality and availability of new information leading to new business models.

Steve Holcombe

Steve Holcombe

Pardalis’ intellectual properties may be strategically compared to Van Jacobson’s impressive research at Xerox PARC (see the CCNx Project) that began in just the last few years. Jacobson's long-range goal is to adjust the architecture of the Internet with immutable named data. Pardalis' IP is focused on sooner commercialization opportunities for changing the Web with immutable, granular named information. But like Jacobson, we view the application of named immutable objects as an absolute prerequisite to authentication in a new world order providing more options for user-centric information sharing.

Steve Holcombe

Steve Holcombe

EOF - Freeing Up Level 7

From Issue #203

Apr 30, 2011

By Doc Searls

Linux Journal

http://www.linuxjournal.com/article/10972

Steve Holcombe | Comments Off |

Steve Holcombe | Comments Off |